by Wilton H. Strickland

During the first Trump administration I wrote an article discussing whether the Constitution requires bestowing automatic citizenship on everyone who happens to be born within the United States, even the children of persons here illegally. This issue has surged back into the headlines because Trump has reassumed office and made a fresh announcement that the children of illegal immigrants will not automatically be recognized as citizens. As before, this has provoked a hue and cry that such an approach violates the Constitution, so I thought it would be worthwhile to share my article again. What I will say up front is that a new approach to citizenship lies in returning to the Fourteenth Amendment’s nature and purpose, which have been forgotten and can be revived without a constitutional amendment (similar to the First Amendment).

As attorneys, our duty is to conduct sober analysis even when times grow turbulent, and sober analysis reveals that there indeed is a constitutional basis for withholding automatic birthright citizenship. It is quite possible — though by no means certain — that the Supreme Court will uphold this approach if given the chance.

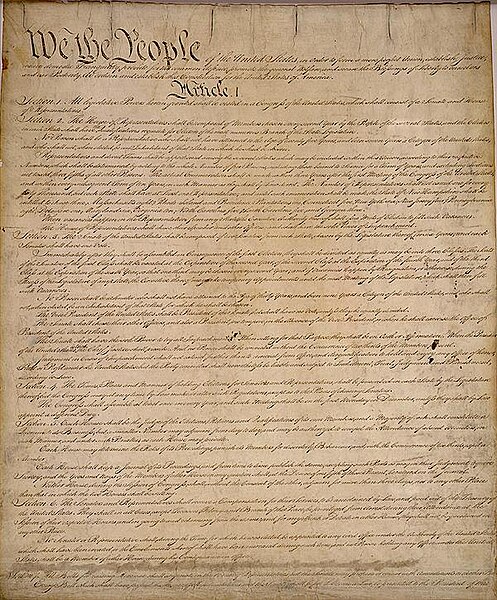

The first section of the Fourteenth Amendment begins with the “citizenship clause,” which reads as follows:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. . . .

The Fourteenth Amendment was approved in the aftermath of the Civil War along with the Thirteenth Amendment (ending slavery) and the Fifteenth Amendment (removing racial restrictions on voting). All three amendments had a “unity of purpose” to abolish slavery and extend full and equal rights of citizenship to the former slaves. Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U.S. 36, 67-72 (1872).

Of particular importance to the Fourteenth Amendment’s citizenship clause was the phrase “and subject to the jurisdiction thereof,” which limited citizenship to children whose parents owed allegiance to the United States. Mere birth within the United States was not enough, since this would extend the privileges and immunities of citizenship even to the children of visiting diplomats or other persons having no kinship with our country. Senator Jacob Merritt Howard, who introduced the amendment for debate, explained as follows:

This will not, of course, include persons born in the United States who are foreigners, aliens, who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers accredited to the Government of the United States, but will include every other class of persons.

Another way of phrasing the function of the “citizenship clause” was provided by then-Senator Reverdy Johnson, who observed:

Now, all this amendment provides is, that all persons born in the United States and not subject to some foreign power – for that, no doubt, is the meaning of the committee who have brought the matter before us – shall be considered as citizens of the United States. . . .

The Supreme Court also took note of the limited reach of the “citizenship clause” as follows:

The phrase, “subject to its jurisdiction” was intended to exclude from its operation children of ministers, consuls, and citizens or subjects of foreign States born within the United States.

Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U.S. at 73.

Not long thereafter, in 1884 the Supreme Court re-affirmed this holding by denying citizenship to a Native American who, although born within the United States, was not subject to its jurisdiction at that time:

Indians born within the territorial limits of the United States, members of, and owing immediate allegiance to, one of the Indiana tribes (an alien, though dependent, power) although in a geographical sense born in the United States, are no more ‘born in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof,’ within the meaning of the first section of the fourteenth amendment, than the children of subjects of any foreign government born within the domain of that government, or the children born within the United States, of ambassadors or other public ministers of foreign nations.

Elk v. Wilkins, 112 U.S. 94, 102 (1884).

A few years later, the Supreme Court issued a somewhat contrary opinion holding that the children of legal immigrants are entitled to automatic birthright citizenship even though they may still be subjects of a foreign power. United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649 (1898). This holding is difficult to square with the Fourteenth Amendment’s purpose and the history of citizenship in the United States, as discussed by the dissent. Even if regarded as completely valid, though, it does not extend birthright citizenship to the children of illegal immigrants, and no subsequent ruling by the Supreme Court has done so.

The current approach of granting automatic citizenship to anyone and everyone born on American soil is not constitutionally required, but rather the result of federal policy that has drifted far from the Fourteenth Amendment. There could be some lingering question whether Trump can unilaterally change the policy or must ask Congress to do it, but either way, the Constitution does not appear to stand in the way (the courts, who are always a tad fickle, might disagree).

I have run into certain arguments against my position, so it’s worthwhile to address them.

One argument is that the Supreme Court’s decision in Plyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. 202 (1982) establishes that U.S.-born children of legal and illegal immigrants are citizens at birth. The actual holding in Plyler is that all persons — whether citizens or not — are covered by the due process clause and the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. There was no holding as to the citizenship clause or as to whether the Constitution requires the federal government to treat children of illegal immigrants as citizens, though there is dicta in footnote 10 stating that the Wong Kim Ark decision should be read this way. Footnote 10 thus constitutes dicta upon dicta, since Wong Kim Ark involved the child of legal immigrants and offers no actual holding or precedent as to the children of illegal immigrants.

Another argument is that the Supreme Court’s decision in Immigration & Naturalization Serv. v. Rios-Pineda, 471 U.S. 444 (1985) establishes that U.S.-born children of illegal immigrants are citizens at birth. The actual holding in Rios-Pineda is that an entire family — two illegal immigrants and their child born on U.S. soil — could be deported under the executive branch’s discretionary power. The decision does refer to the child as a citizen, but it does not discuss (or issue any holding about) whether the federal government is constitutionally obligated to treat the child as such. The holding does quite the opposite by blessing deportation. At most, the reference is based on federal policy toward such children rather than a constitutional analysis of that policy.

Admittedly, there is ambiguity surrounding the phrase “subject to the jurisdiction thereof,” whose meaning is not plain on its face. Such ambiguity requires looking at the evidence surrounding the passage and implementation of the citizenship clause at the relevant time, and the evidence shows that the clause was meant to grant citizenship to former slaves rather than to the children of visiting foreigners. Wong Kim Ark deviated from that, but only to a limited extent that does not extend to the children of illegal immigrants.

Last but not least, it bears recalling that the Supreme Court is merely one branch of the federal government and inferior to the Constitution. If the co-equal branches of the President and the Supreme Court wind up at odds on this issue, perhaps Trump can steal a page from former President Andrew Jackson, another populist he often has been compared to: “John Marshall has made his decision. Now let him enforce it.”

UPDATE

Well, that didn’t take long. A federal judge in Seattle has blocked the administration’s new policy of withholding birthright citizenship from the children of people illegally within the United States, denouncing it as “blatantly unconstitutional.” It is unfortunate that some judges — and federal judges, no less — display this level of ignorance.

But there is more than ignorance at work here. It is an entire mindset that infests the legal profession and begins in law school, where students are taught that the Constitution has no objective meaning and is mere putty in the hands of jurists, who can alter and update it without regard for the amendment provisions thereof. According to this worldview, the fact that the federal government for a long time has bestowed birthright citizenship on anyone and everyone born within our borders means that this approach is now required by the Constitution. This worldview does not dare to consider that the longstanding federal policy is wrongheaded and rogue, since that would mean that the federal government cannot perpetually reinvent the Constitution at will.

What is at stake here is far more than birthright citizenship. It is whether we have the rule of law or the rule of lawyers. I have written articles and books on how I believe we no longer have the rule of law, but I would enjoy being proven wrong if the federal government ultimately gets this particular issue right.